Put together by the fashion museologist Judith Clark and the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, Barbican’s latest exhibition The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined presents a visually well-curated and thought-provoking stage for visitors to wander around, wonder about and ponder on “the vulgar”.

The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined exhibition catalogue by Charlie Smith Design Illustrations by Alice Smith

Gigantic hats, glitter, overuse of lace, pop culture inspired paper dresses, flesh revealing bodystockings : what is considered “vulgar”? Is it simply bad taste or is it a bigger subject matter that revolves around class, sex, commercialism and exhibitionism? Barbican explores these questions in its latest exhibition: The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined, which features 120 exhibits from couture to ready-to-wear designers. This broad theme, which is also one of the most challenging territories in fashion, pushes the boundaries of definitions, eras and styles and encourage visitors to explore the term beyond its ‘common’ meaning.

Vulgar, vulgarism, vulgarity, vulgarly From the very first section of the gallery, the show feels like a trip through a 3D fashion encyclopedia that is set up by themes rather than chronological order. Starting off with the literary definitions (“Vulgar” was originally associated with “common” as “Vulgas” meaning “common people” in Latin), it covers over 500 years of historic dress, pret-a-porter and haute-couture as well as the events and names that have shaped the perception of taste in fashion. In the purpose of proving that the definition very much depends on perception of individuals, the display daringly clashes those different perspectives and opinions through the works of Coco Chanel, Diana Vreeland, Jonathan Swift or Samuel Johnson.

According to psychoanalyst Adam Phillips, who is also the co-curator of the exhibition, “the vulgar, like fashion, is always a copy. It invites us to imagine the original and exposes what has been lost in translation. In this way, the vulgar restores our confidence in the purity of the source.” Echoing this relationship mentioned between copy and the vulgar, the first section Translating the Vulgar includes ‘Cretoise dress’ designed by Karl Lagerfeld for Chloe, which suggests mythologised Greek and Italian historical elements through some “pretty” folds and drape details. Similarly, iconic Mondrian Mod style Yves Saint Laurent dresses from 1960s beautifully lays Mondrian’s straight lines on female body form.

‘The vulgar and the fashionable have to keep an eye on each other’

Although the section titles and object labels make each theme and the reason why the particular pieces were chosen for those sections pretty clear, if you somehow fail to notice them, some gowns might make you wonder how they ended up in an exhibition called “the vulgar”, such as delightfully simple Grecian style Madame Gres designs from the 70s, which aim to give an idea of how mass-production has been associated with vulgar. Another example from this section is the fan: an object of desire which was formerly preferred by the elite but then lost its status value once mass production made it available to wider user group.

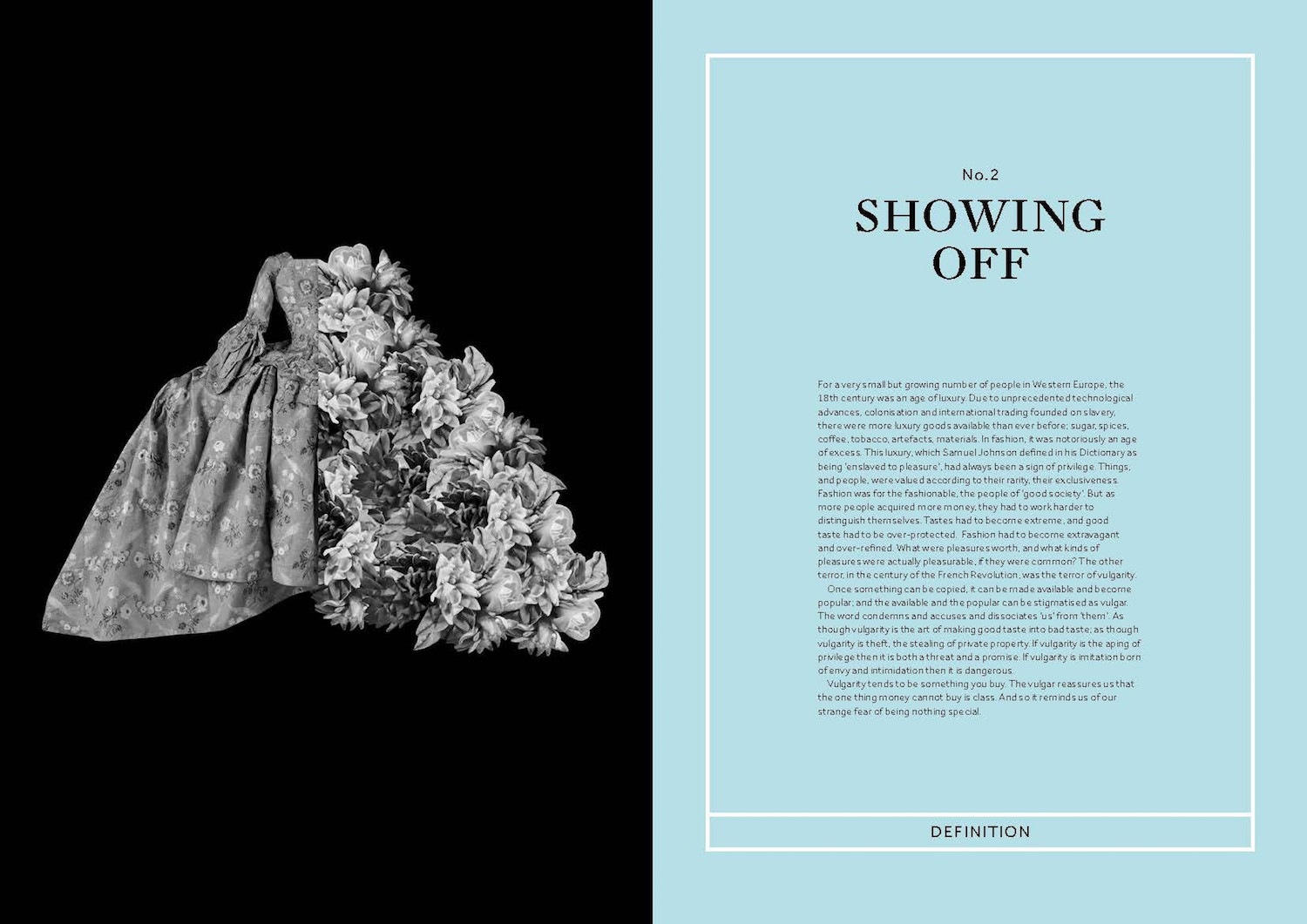

The majority of the pieces exhibited in the show, though, don’t hesitate to glamorously justify their presence in the display. After all, in an exhibition that deals with the concept of vulgarity, it is hard to find a piece that doesn’t catch your eyes. For example, it is not quite possible to miss some attention-seeking wide -almost as wide as the gallery corridors- 18th century dresses loaned from Fashion Museum in Bath. It’s also an odd but interesting mix to see an 18th-century Court Mantua dress next to a Christian Dior gown designed by John Galliano in 2005.

This well-balanced contrast among the artifacts is not only specific for the centerpiece section Showing Off, but could also be observed and enjoyed throughout the entire show. Karl Lagerfeld’s leather shopping basket design for Chanel follows up a ‘Souper Dress’ from 1960s inspired by Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans delving into consumerism and the concept of shopping. Further on, exploring the relationship between fashion and the body, another section offers Vivienne Westwood’s two famous pieces: ‘Eve’ (nude body stocking with fig leaf) and ‘Boucher’ courset. This theme explores over exposure, revealing the body as well as the exaggerated body, where the body’s specific zones are amplified and exhibited in focus, such as Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s ‘tits top’ and Walter van Beirendonck’s elephant skirt (2010-11) topped by an oversized red velvet Mad Hetter hat by Stephen Jones.

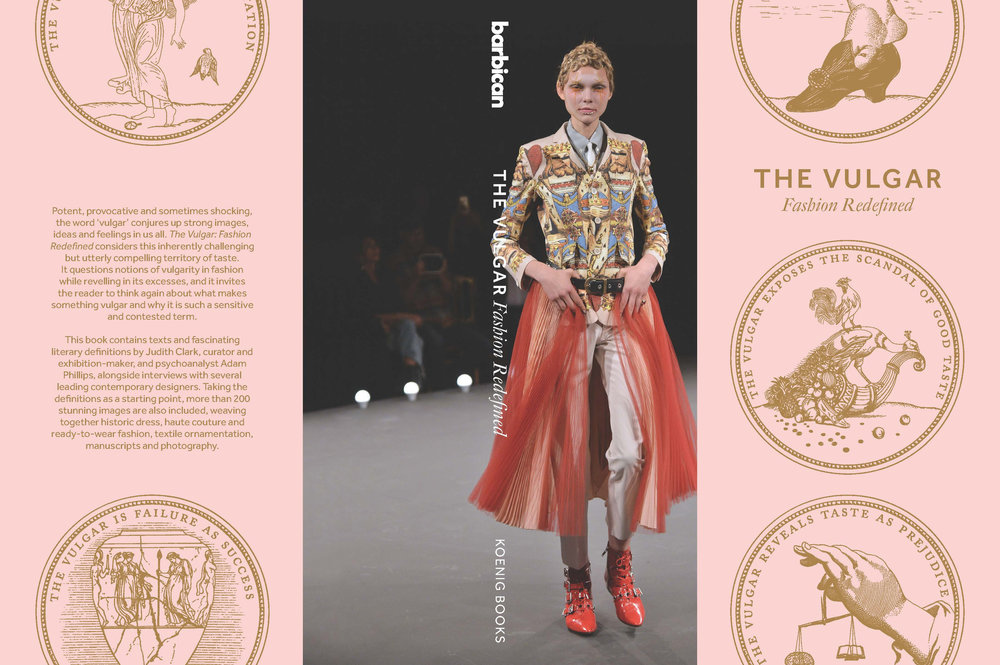

“Vulgar" Catalogue Not as vulgar as the theme suggests though, the exhibition catalogue with gold and pale pink cover is thoughtfully designed by Charlie Smith Design. It includes over 200 images, textiles and manuscripts from the exhibition. The emblem illustrations by Alice Smith, which are featured on three large-scale coin sculptures situated throughout the exhibition are also seen on the cover. Smith’s Tarochi cards inspired graphic interpretations of the texts are definitely one of the strongest and the most interesting elements of the show. The Vulgar also touches on some previous Barbican exhibitions, such as The Fashion World of Jean-Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk (2014), Future Beauty: 30 Years of Japanese Fashion (2010) and Jam: Style+Music+Media (1996). This retrospective approach could also be interpreted as Barbican’s way of self-criticizing in terms of questioning fashion’s place in an art gallery; the commercial aspect of these big fashion shows and putting brands under a roof of an art institution.

This is also a good place for visitors to stop and think the display as a whole before they leave the gallery. Left: Walter Van Beirendonck’s Elephant outfit from “Take a Ride” collection (2010-2011) with a red velvet hat by Stephen Jones, Right: Mondrian inspired dress by Yves Saint Laurent (Credit: Michael Bowles/Getty Images) Stephen Jones: “What we must never forget is that the vulgar is tremendous fun” Even though we can’t put “the vulgar” in a certain definition or tie it down in a formula, vulgarity seems like a concept that doesn’t go away over centuries but rather change its form, agency and actors. There is no doubt that it will always be defined from personal perspectives and subjectivity will shape its contradictory nature. And this ambitious show on vulgarity attempts to use this subjectivity and challenge the perceptions about how it was defined before and what it means today. Maybe the scale of the question of “what is ‘vulgar’?” seems to be too big for one single fashion exhibition to answer, which can be seen in the lack of non-Western and menswear examples in the exhibition. However, the meanings and perceptions that “the vulgar” conjures up make the subject open to further exploration and it is mainly what makes the shows exciting, thought-provoking and challenging but maybe not inspiring; because like Phillip suggests “As the scapegoat of good taste, the vulgar does a lot of work for us. And like all scapegoats, it must not inspire us.”