Re-framing the bubbles

Even though this sounds like a cliche, to me, home is people rather than spaces. I feel more at home when I’m challenged - by people, new places and experiences.

Portrait: John Gribben / Interview: Yağmur Rüzgar

Jordan Söderberg Mills is an interdisciplinary artist and maker with a background in blacksmithing, with a hands-on studio practice. He believes that the objects he makes don’t fit into traditional categories. Jordan was one of the speakers in our “Design for a Phygital World” panel series. While figuring out new ways of thinking, producing and designing, we questioned how moving in-between different cities has affected his practice.

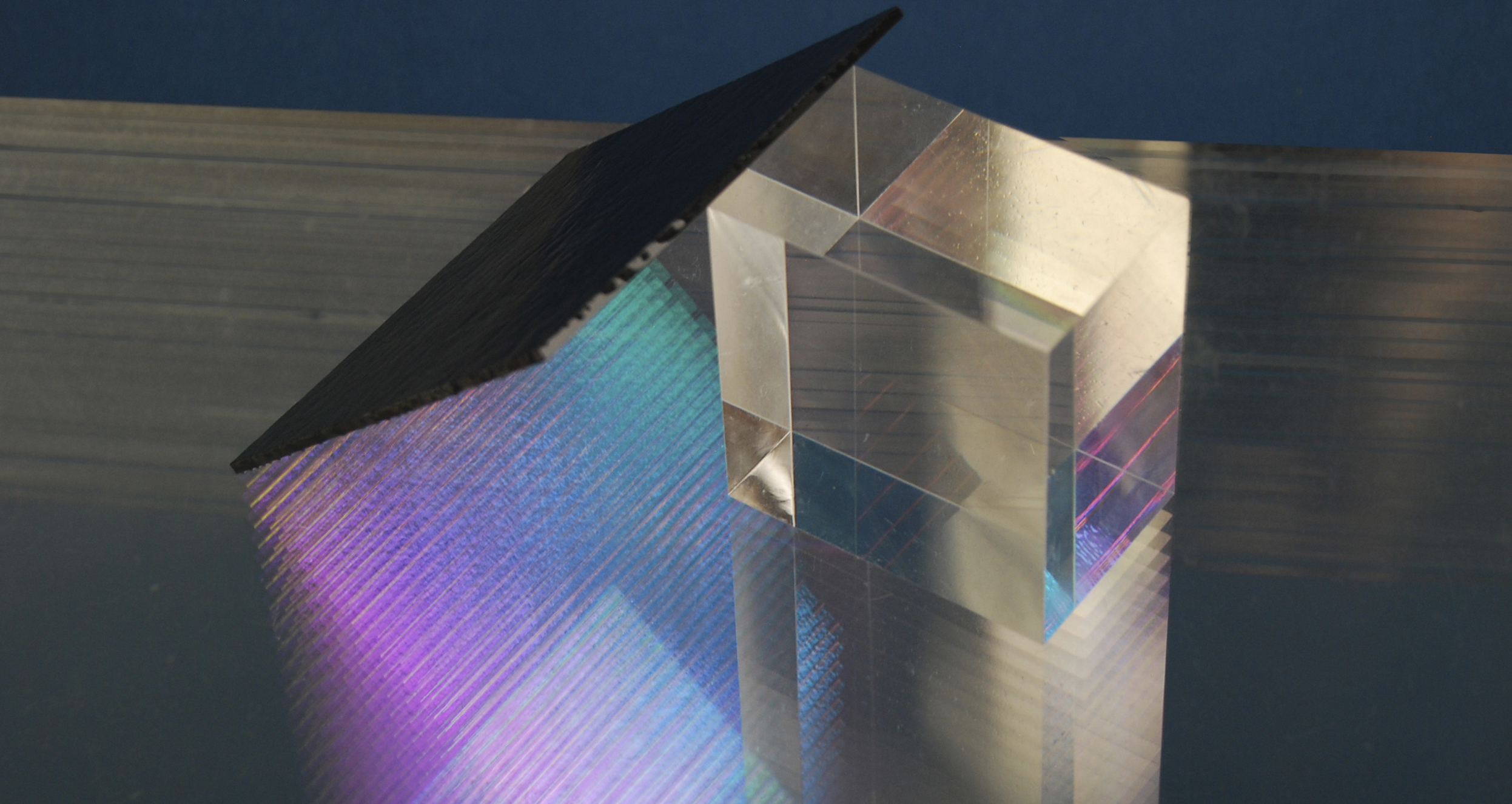

Parabola, 2016

Firstly, I’d like to ask your perception about the concept, “phygital”. What is “phygital” for you?

I’d never heard of the term “phygital” until I was invited to be a part of Frame Magazine’s exhibition at Milan Design Week this year. I honestly didn’t realize that this was what I was already doing. My work plays with the transition between material realities and subjective experiences. The idea of the “phygital” is just that: objects that lie between physical and digital realms. I’ve always been a little intimidated by computers - they operate in a language that I don’t know - but I find their possibilities so interesting and compelling - they can play with vision, generate illusion, even create a sense of magic.

My work is actually very based in physics but allude to these computational realities. I’m looking at early experiments of optics, people like Isaac Newton, Al Hazen, and Epicurus, investigating the world through empirical science. These are ancient methods interrogate the world around them, seek understanding, and create science as phenomenon - generating objects and experiences that call attention to the peculiarities of the physical world.

Diffusion series, 2015

You were born in Toronto, studied in Santiago and got your master degree in London. How did these completely different cities effect your creation process?

I’m really interested in things that lie between states. I always knew that I was weird and different while growing up and I didn’t fit into a lot of things. I think that’s what motivated me to travel - I had an excuse to be different.

What I discovered is that when you move to a new city, you’re hyper aware of everything - from the texture of the grass, to the accents of the seagulls. You start paying attention to your own perception, the way you’re looking at things. I think that had a lot to do with opening up my eyes. Feeling like a stranger, and being hyper aware - these were the states of mind that pushed me in my art practice. It was like trying to understand my position in the universe.

Traveling reframed my emotional and perceptual experience of the world. I grew up in one place and I had this bubble of information around me which wasn’t the whole story. For me to move to Chile, or London was a way to get more versions of the story.

My work is about trying to capture information and perspectives that are invisible to us, these bits of the world that we’re not seeing. I try to open up this awareness through physics and optics, by literally by expanding our vision. Our perceptual reality is a bubble, and it reveals only a small percentage of what’s happening around us. The universe we experience our whole life is not the actual universe that exists. It’s not the whole story. I try to show that these bubbles are actually an ever-expanding foam.

Parhelia, 2016

Your studio practice is based in these three cities. Has being “based” lost its physical meaning?

I do bounce around quite a bit. I’ve been very lucky in this sense. While making physical objects, I need to have a physical space to work with access to tools. Generally if I have a show in a specific city, I go and spend time there to make and build, which means I’m based wherever I have exhibitions. I have to have my own space and my hands on the work, this is very important for my practice.

I’m “based” in workshops, with three spaces that I move between. London feels like home at Blackhorse Workshop in Walthamstow - I have a shared working space where I’m always invited. In Chile I have a home and forge, and work in more chthonic materials like stone, wood and steel. I try to spend the winter there. In Toronto, I have a glass workshop, shared with two other makers.

As an artist, I want people to see the work, engage, ask questions, and challenge me. I try to take advantage of opportunities as they present themselves or as I generate them, which has taken me all over the world.

Do you ever feel in-between or is it more like something that feeds you?

Always. I always feel in-between. I mean this in a philosophical and a geographical sense - at first I believed this was a source of weakness but I’ve tried to turn it into a strength. I now feel more at home wherever I am but, even though this sounds like a cliche, I actually think that home is people rather than spaces. I feel more at home when I’m challenged - by people, new places and experiences.

Does being an interdisciplinary artist also mean being an international artist today?

I’ve always been interested in the intersection of different fields. Art and design, architecture and craft, science and the occult. Things like magic, monsters, mythology and apocrypha - things that pose questions of reality versus fantasy. Stuff you can perceive and not perceive, stuff that lies at the border of our understanding.

The idea of being an interdisciplinary artist is to straddle these borders. It’s the idea of not being limited by expectations, a particular label, location or category. I don’t want to restrain the outcomes of my practice or the places where I work. I call myself an artist, but I try to interrogate my surroundings like a scientist, build my ideas like a craftsperson and strategize my ambitions like an entrepreneur. I’ve been lucky that my work has resonated in different places in the world which to some extent has contributed to my practice of working between states.

As an “interdisciplinary artists” we should be able to transcend traditional limits: make a collection of furniture, collaborate with the ballet or opera, direct a music video or play with fashion. As a creator, it’s a good idea to operate like an entrepreneur - find all the ways to spin out your ideas, collaborate, travel and work where people respond to your ideas.

It’s convenient to say that you’re an interdisciplinary artist and work within design, craft, scientific fields or fine art contexts. I’ve had my works shown in design and fine art museums across the world because the objects I’m making don’t fit into a proper category. It’s design or art, either or both. I don’t mind how it’s labeled. It’s the product of my instincts which tend to lie in-between the margins of things.